By Robert L. Moore, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief Medical Officer

“The Half-Life of Knowledge: The amount of time elapsed before half of the knowledge in a particular field is superseded or becomes obsolete.”

– First described by Fritz Machlup in 1962

About 25 years ago, I read an article that looked at the current recommendations for a variety of medical conditions and circumstances. Over time, these recommendations change, gradually at first, then more rapidly and finally slowing down as a few best practices persist over the decades.

Those of us who have been in practice for a while can think of many examples. Few in the United States use the medications for type 2 diabetes that I used as a resident physician. Vaccine recommendations change, but many vaccines haven’t changed in decades. Suspected appendicitis used to invariably mean surgery; now many cases are managed with antibiotics. Hormone replacement therapy was prescribed long-term for most post-menopausal women years ago. The list is long.

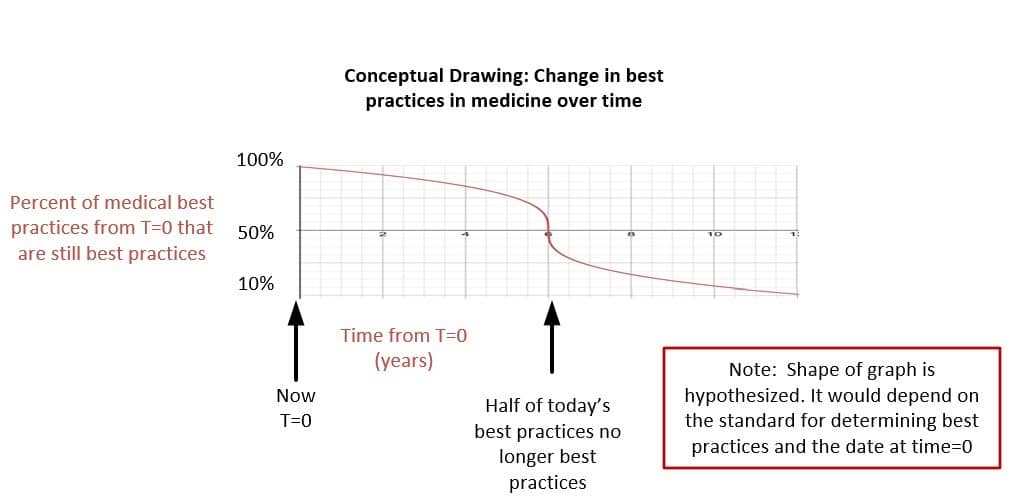

Twenty-five years ago, the half-life of medical knowledge was estimated to be six years based on a review of all recommendations made in a group of best-practice documents released by CMS (this was the predecessor to the USPSTF). This meant that if you failed to keep up with the latest developments, half of what you did today would be incorrect in six years and 90% would be incorrect in about 12 years. The decrease is not constant. Here is a graphical representation of the way I think about this with the X axis in years from today (T=0), and the steepest part of the decrease being at 6 years (50% of current best practices at T=0 are no longer best practices; the half-life).

The shape of the graph reflects the fact that published best practices are not updated continuously, but on a cycle of every few years. Thus, the slow downward slope initially.

A couple of implications of the shape of this curve jump out. First, if one assumes that the peak of one’s knowledge of best practices is at the end of formal clinical training, for the first few years, the knowledge you have from residency will serve you well. If you don’t adopt a system for keeping up on changes, however, the subsequent years will make you quickly lose touch with how best to practice medicine. Second, if someone takes a break from clinical medicine for up to 2-3 years, they will be able to get back up to speed quickly. A longer break will require more extensive re-training, mentorship and formal education.

A study in 2011 estimated that the half-life of medical knowledge had dropped to 3.5 years. It seems likely this trend has continued, especially in the age of COVID.

There are three primary strategies for maintaining high quality care in this setting.

1.) Diligent self-education, regularly reading medical journals in your area of expertise, and attending (and paying close attention to) conferences that summarize updates in your field. For primary care clinicians, American Family Physician is a good resource.

2.) Liberally use the rapid on-line resources we now have available to check on current recommendations for any condition that is somewhat infrequently seen, and for which you haven’t recently read a review article or attended a presentation. Up to Date is an excellent option, although the American Family Physician website gives rapid access to previous review articles that are often more accessible.

There is a new variation on Board Certification examination for Family Physicians in which difficult clinical questions must be answered within two minutes, using any computerized resources you like. This reinforces this ability to think about where to find the best answer quickly, but critical thinking is definitely needed to sift through all you find to come up with the best plan.

3.) Interact with clinician colleagues regularly, and “talk shop”. Clinicians will remember well lessons learned from peers. Back when primary care clinicians rounded in the hospital, this interaction with many different specialists happened regularly. Now, you will need to seek out peers if you want to have these interactions.

In all cases, we must be humble about what we know about diagnosis and therapeutics. Use the computer in your exam room to quickly confirms that your treatment plan is the best. I find that patients are reassured by this. Find ways to talk to colleagues about the most challenging cases, perhaps at peer review rounds, morbidity and mortality reviews, or even at a Balint group.