By Robert L. Moore, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief Medical Officer

“The art of scheduling lies in balancing supply and demand.”

– Rosemarie Nelson, Medical Group Management Association

Note to readers: This month’s lead article is more quantitative than usual. I tried my best to make it accessible, but to fully grasp it, I do recommend reading it at that time of the day when you are most alert!

Many clinical quality measures lend themselves to year-end “sprints” where staff call up patients to encourage them to complete mammograms, cervical cancer screening, blood pressure checks, blood tests, etc. – typically from early October through December 31.

Theoretically, well-child visits could also be the focus of a year-end “sprint,” but this rarely works, for several reasons:

- Toward the end of the year, holiday plans mean families would rather wait until the following year to schedule the visit.

- Clinicians also take needed time off for the holidays, leaving the covering team understaffed while caring for acute problems with reduced capacity to deliver preventive care.

- By November and December, respiratory infections start increasing sharply, constraining the number of available appointments for well-child visits.

- So few well-child visits are completed within the first nine months of the year, that it causes many children to be overdue at the end of the year without enough time in the remaining schedules for them all to be seen.

The last scenario is common for Quality Improvement teams at Primary Care Provider (PCP) offices visited by Partnership’s Performance Improvement team. Several practices feel a sense of hopelessness towards the idea of catching up before the new year begins. (See Clinic A below)

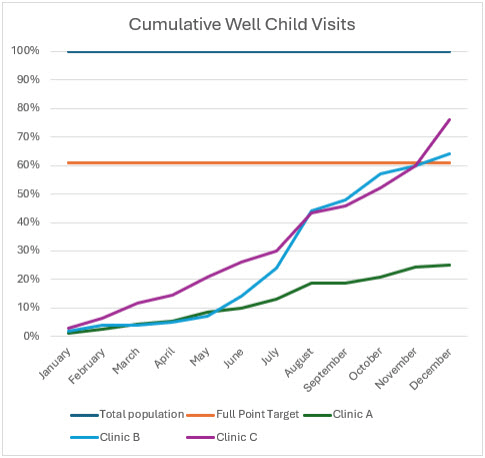

Real data from three sites in 2024 shows this pattern of visits for Clinics A, B, and C, shown on the next page.

Clinic A averaged just 2.1% of their total population with a well-child visit each month, steadily maintaining that rate throughout the year with no discernable effort to catch up. Their scheduling of well-child-visits was rigidly inadequate with possibility for flexing the schedule to catch up. When they analyzed their gap in September, they were so far from target that they had no hope of catching up, so they did not try.

Clinic B had a slow and steady rate from January through May, with a concerted effort to increase visits in June through August. From September through December, the rate continued to rise steadily, achieving the goal in December.

Clinic C averaged 3.4% of their total population through July. At that continued rate, they would never have reached their target. However, they began a big push for August through December, with an average of 9% for the last five months of the year, ultimately beating the target by 15%.

A practice that was determined to achieve the target, but to have a completely steady number of well[1]child visits per month, would have to see 5.1% of their pediatric patients aged 3-17 every month to achieve the goal of 61% by the end of the year. I could not identify any primary care office in Partnership’s 24 counties that had 5% per month or more of their pediatric patients with a well-child visit in the first few months of the year.

While Clinics B and C reached the target, they expended significant effort to catch up in the second half of the year, starting in June and August, respectively. This corresponds to the summer break from school, when scheduling well-child visits is a bit easier. However, in both cases, significant effort continued from September through December to achieve the full point target.

How does this scheduling pattern compare to the demand for visits for acute illnesses?

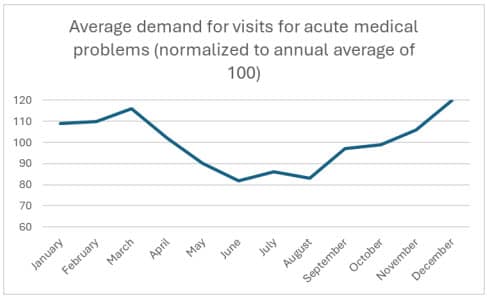

In their article measuring the demand for same day visits for acute problems in 2001, Forjuob et al (2001) describe that such visits varied significantly by month of the year:

In this normalized data, same day appointment demand ranges from a low of 80 to a high of 120 visits per day. Starting in late April, you may see a reprieve from the scheduling pressures due to seasonal upper respiratory infections.

The lowest demand for visits for acute problems is between May and August. November through March has the highest demand for such visits, corresponding to the typical pattern of seasonal respiratory illness.

Not shown in this graph is the variation by day of the week, with Monday having an average annual demand of 123 and Wednesday having an average annual demand of 91.

In developing a weekly schedule, fewer well-child visits should be scheduled on Monday. You can access an Excel spreadsheet with the daily data here.

Why don’t well-child visits start rising in April, as the respiratory infection season starts easing? This would seem to be a logical time to start increasing well-child visits, instead of waiting until the busiest month of the year (December) to heroically reach the target.

The answer is recency bias, in which our minds give greater importance to the most recent event. In March, when we are opening our schedules for the next few months, we are in the fourth month of very busy schedules, working late every day. It seems like it will keep going like this forever. We forget we are on a predictable downslope in demand and don’t start ramping up our summer schedule for appointments until we notice fewer people are calling in for same-day appointments; same-day appointments are not always full. We then adjust our schedules to accommodate more well-child visits, keeping this schedule into November or December to achieve our preventive-health[1]visit targets, even as the schedule starts getting busy again.

Planning ahead for the predictable decrease in demand for acute/same-day visits starting in late April, and then steadily increasing the number of well-child visit appointments from April through June, will help spread out the workload. This can make a big dent in the number of well-child visits needed, so an end-of-the-year sprint has a better chance of succeeding.

Planning your schedule for well-child visits at the beginning of the year, taking into account demand for same-day visits as well as staff time off, can set your office up for success in reaching the target! From late April through June, consider a mid-year sprint effort focused on scheduling well child visits before summer vacation schedules begin to limit appointment access.