By Robert L. Moore, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief Medical Officer

“Current models of health care funding, which treat health care as a service for an individual rather than as infrastructure for a population, are innately biased in favor of large populations.”

– Janice Probst, Jan Marie Eberth, and Elizabeth Crouch in Health Affairs, December 2019

Preface: Just as the COVID-19 infections began to spread in December 2019, a seminal article was published in Health Affairs, coining the term: structural urbanism.

In the article Structural Urbanism Contributes to Poorer Health Outcomes for Rural America, the authors define structural urbanism as “elements of the current public health and health care systems that disadvantage rural communities.”

The COVID-19 pandemic consumed our attention for several years, contributing to changes in the way we think, teach, learn, work, and act on public policy. In the Spring of 2020, a series of police killings sparked national protests seeking greater racial equity and a governmental and corporate focus on racial justice. As rural hospital obstetric unit closures continued and Glenn Medical Center closed altogether in 2025, it has become more significant that the Partnership counties reframe the way we think about rural health policy.

To re-ground us in this reframing of rural health policy in February 2026, I present my January 2020 lead newsletter article on this topic, lightly edited and updated. The Health Affairs article referenced above is available online for free and is highly recommended for reading. The reflections below become an inspiration on how structural urbanism impacts Partnership and our rural clinicians and members.

Enjoy!

In January 2019, the California Department of Health Care Services (DHCS) decided that all providers that contract with Partnership HealthPlan of California and other Medi-Cal managed care plans must apply to the state of California and be accepted as official Medi-Cal providers. Previously, Partnership could contract with specialists outside the state in Oregon and Nevada, which is closer to our members that live in border counties. These out-of-state specialists are excellent physicians to partner with and are recognized by Medicare and the state Medicaid organizations in which they practiced. The DHCS decision was not required by the federal government, but it was based on administrative convenience. The needs of Medi-Cal beneficiaries in border regions were not considered sufficient enough to alter the policy.

This is an example of structural urbanism.

This can include policies and regulations, such as the rule on out-of-state specialists which limits access to care for those in rural communities.

It can also include the fee-for-service payment methodology, which pays hospitals based on volume. Smaller rural hospitals have far more fixed costs per admission, so an “equal” payment arrangement becomes a disadvantage for smaller rural hospitals, contributing to financial instability and hospital closures. This is yet another example of structural urbanism.

It can also extend to state grant programs, like the Public Hospital Redesign and Incentives in Medi-Cal (PRIME) program. This specific program designated payments to public hospitals, which are all situated in counties with large urban populations. While some version of this may be adapted to smaller counties, at best, only medium-sized counties have the infrastructure to access these funds, and yet again, serves as another example of structural urbanism.

Structural urbanism impacts county social services infrastructure which, in turn, affects health status.

Structural urbanism affects primary care access. National Health Service Corps loan repayment eligibility is dependent on the Health Professional Shortage Area score (HPSA score), which supposedly measures the relative need for physicians in a particular area. The score in parts of urban Los Angeles County is higher than many rural areas in Northern California. While urban health centers serving low-income areas need providers, the providers are able to commute from areas with higher average income. In contrast, rural California health centers need to convince new clinicians to move to a new area. The scoring methodology does not account for this, which is another example of structural urbanism.

Decades ago, sociologists coined the term “structural racism” to describe the historic, political, and social structures that perpetuate racial inequality. Structural racism contributes to persistent health disparities experienced by marginalized racial and ethnic communities. Opposition to a structural racism framework often centers on the belief that persistent inequities stem from individual choices, reflecting the assumption that personal motivation alone can overcome systemic barriers.

Racism is not always just structural, resulting from implicit bias, but is sometimes explicit. Similarly, we may encounter examples of explicit urbanism. Here are three examples:

With today’s political polarization and the increased association of rural areas with support of conservative voting patterns (including in California), some policymakers are explicit in not wanting to prioritize rural areas in any way due to political affiliations.

In the medical field, I have encountered Obstetrician / Gynecologist (OB/GYN) specialists and OB nurses who believe that becoming pregnant while living in rural areas is a high-risk choice for women rather than a policy challenge to rectify. (This explicit urbanism is not universal. Many other OB/GYN specialists and OB nurses have expressed understanding and support for policy and structural solutions to ensure rural OB services are available and safe given inevitable volume and distance influences.)

In state government, we have heard a policymaker remarking on rural specialty access challenges with the suggestion that people who need specialty care should move to large metropolitan areas (indicating a deep lack of commitment to restoring robust specialty access to rural areas).

There is a conceptual similarity between structural racism and structural urbanism. Health outcomes in rural populations have complex and interrelated structural factors. Are worse health outcomes due to the “choice” to live in rural areas? Are they due to poverty itself? If so, why do low-income populations in urban and suburban communities have better outcomes than low-income populations in rural areas? How does differential access to social services, charitable organizations, and health care providers associated with rural areas contribute to differential outcomes? These many factors are the manifestations of structural urbanism.

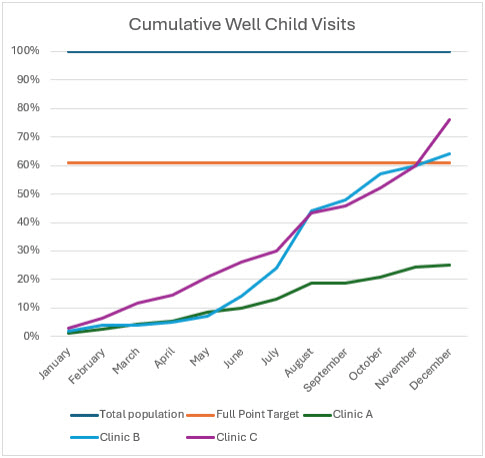

We can measure worse health outcomes in rural counties. Each year, after conducting our annual audit of the Health Effectiveness Data Information Set (HEDIS®), we stratify the results based on the demographic information we have available. Specifically, we are looking for different outcomes associated with any race, ethnic or language group, and geography. Since 2014, we have found outcomes vary by geography more than race, ethnic or language groups, with the exception of outcomes in the Black and Tribal populations.

Studies suggest rural health inequities are driven by several factors, including less availability of health care and social services, higher poverty levels, higher rates of substance use disorders (SUD), and different health beliefs and practices. These are incompletely balanced with resiliency factors associated with living in small, tighter knit communities.

HEDIS® outcomes in rural areas have improved gradually year over year, but the geographic disparities remain.

How do we achieve better outcomes for rural counties? How do we overcome structural urbanism?

The Health Affairs review article mentioned above has several recommendations:

Access: Maintain and increase availability of health care providers and institutions in rural areas.

Conceptualization: Change the conception of the provision of health in rural areas from being a service to being infrastructure. Decades ago, rural hospitals were funded by the federal government as infrastructure and were able to grow and thrive. Since the conversion to a fee-for-service environment, rural hospitals are closing and quality measures for rural hospitals (which previously were equal to urban hospitals, in aggregate) have steadily declined.

Resources: Additional financial resources can help reduce rural inequities. The National Health Service in England created such a financial redistribution method in the 1970s and 1980s to provide additional resources to rural areas, resulting in decreased access disparities from 22% to 6% in a 12- year period.

Partnership is dedicated to addressing structural urbanism at multiple levels: interventions to increase provider access; leveraging funding mechanisms to provide differential support to rural health care providers; and addressing social issues which impact health (like housing instability, substance use, and justice-involved status). We will also strive to give policy input and feedback from a rural perspective to DHCS and other state agencies, whenever possible.

Correcting many other contributors to structural urbanism will require legislative and regulatory changes at the state and federal levels. Defining a prioritized policy agenda will require us to work together with our partners in rural areas.

Acting on a rural policy agenda is challenging, as organizations working in rural areas often have fewer staff and less resources available to do advocacy compared to urban organizations. For example, compare the organizational structure and capacity of the Consortium of Clinics of Los Angeles County with the California State Rural Health Association (CSRHA). These differential capabilities are also examples of structural urbanism, but organizations representing rural health policy interests are arguably the key to changing the discussions around rural health.

We need organized, effective advocacy to promote rural health equity.

Organizations such as the CSRHA, the California Rural Indian Health Board, and the California Critical Access Hospital Network need more active members and leaders to build infrastructure and generate the policy influence to counteract structural urbanism.

The boards of state-wide organizations like California Health Care Foundation (CHCF), The California Endowment, and the Blue Shield of California Foundation need vocal rural representation to help vet priorities and proposals from a rural lens.

It takes a stronger effort for leaders living in rural areas to engage personally in such organizations, compared to their urban colleagues. This is partly due to travel time, but additionally, rural hospitals and clinics may have a smaller core leadership team who also need to optimize care and operations locally.

Building rural health care leadership is thus a key prerequisite.