By Robert Moore, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief Medical Officer

Clinical Case: A 23 year old woman with a several year history of gastritis (with prior treatment for H. pylori), migraine headaches, geographic tongue and anemia has a complete blood count ordered by her primary care physician, finding a hemoglobin of 9.7 with microcytic indices. She has an uncle with gluten intolerance, first developing these symptoms after being treated successfully for H. pylori-associated duodenal ulcer disease.

What is the probability that this woman has Celiac disease? What does Helicobacter pylori infection have to do with Celiac Disease? What is the best first test to perform?

Celiac Disease is an autoimmune disease affecting about 1% of the U.S. population, but 83% of these individuals are either undiagnosed or diagnosed with other conditions without making the link to the underlying Celiac Disease. Of those 17% who are diagnosed, the mean time between onset of symptoms and diagnosis is between 8 and 11 years. It is arguably the most underdiagnosed and misdiagnosed condition in the United States, although this is beginning to change, thanks to new genetic and antibody tests that help point to the right diagnosis before doing a confirmatory duodenal biopsy. Primary care providers need to know what signs, symptoms and blood tests should prompt further workup, and how to do the initial, low-invasive testing.

On the flip side, there are a growing number of people who have (or believe they have) gluten intolerance, who do not have Celiac disease.

The history of the discovery of Celiac Disease is a case of an astute clinician making an observation under conditions of a natural experiment.

In the 1930s, Dutch pediatrician Willem Dicke was studying a mysterious, often fatal disease among children, where they were losing weight and malnourished in spite of plenty of vitamin-rich caloric intake. While he suspected this malabsorption syndrome was related to diet, he was not able to pinpoint the culprit until the winter of 1944, during World War II. Dutch railway workers held a strike in support of the Allies, prompting the Nazis to cut off food shipments to Dutch civilians, which led to mass starvation, except for Dr. Dicke’s pediatric patients, who actually got better.

During 1945, the allies parachuted bread to Holland, ending the Hunger Winter, ending the starvation, but Dr. Dicke’s patients immediately relapsed. He hypothesized that grains were the cause of the malabsorption syndrome. He performed an experiment on the children, putting them on a gluten free diet, showing that the symptoms were completely gone, then put them back on a regular diet, showing that the symptoms came back.

Causes of Celiac Disease: As an autoimmune disease, there is a combination of a genetic predisposition and environmental factors.

- Genetic: In terms of genetic predisposition: 95% of those with Celiac Disease have a gene called HLA DQ2, and most of the remainder have HLA DQ8. However, of those individuals with either the HLA DQ2 or HLA DQ8 genes, only 3% have Celiac Disease.

In summary, although negative genetic testing can rule out celiac disease, a positive test cannot confirm the diagnosis.

Thirteen additional genes are associated with an increased risk that those with DQ2 or DQ8 will develop Celiac Disease.

Among first degree relatives carrying the DQ2 or DQ8 gene, 30% of symptomatic first degree relatives have Celiac Disease, and 10% of asymptomatic first degree relatives also have the disease found on intestinal biopsy. Overall, between 5 and 22% of individuals with Celiac Disease have a first degree relative who also has Celiac Disease.

- Exposure to Gluten: The incidence of Celiac Disease is higher in populations with larger consumption of wheat. Thirty years ago there was literally an epidemic of Celiac Disease in Swedish infants, when low rates of breastfeeding combined with standard use of wheat in infant formula, which led to diarrhea and failure to gain weight. In the 1980s, Celiac Disease was widely recognized and diagnosed in Italy, a country with a culinary culture of pasta, bread and pizza dough, all rich in gluten. Northern India (which consumes more bread) has a higher rate of Celiac Disease than southern India, where rice is the staple.

- Protective Factors: When genetic factors and diet are the same, the incidence of Celiac Disease is lower in lower income populations compared to higher income populations, as found in epidemiological studies. Using stored serum samples, researchers have found a four-fold increase in incidence of Celiac Disease over the past 50 years. While overall income has increased in that period, what is the underlying cause for this association?

An epidemiological study published in 2013 suggests one potential mechanism for this finding: Helicobacter pylori infection, whose incidence is higher in low income populations, is associated with half the rate of Celiac Disease. Increased recognition of H. pylori infection as a cause of gastritis and peptic ulcers has led to widespread treatment, solving one problem but potentially increasing the risk of another. There may be other protective factors related to other bacterial flora which we do not yet understand.

Clinical Diagnosis:

Many common conditions of the intestinal tract and elsewhere in the body may be associated with Celiac Disease, either directly by the autoimmune process, mediated through the resulting malabsorption/malnutrition/vitamin deficiency or associated with the psychological stress of the other symptoms. These include:

- Vitamin deficiencies (Iron, B1, B12, A, D, E, K etc.), with symptoms associated with these deficiencies (easy bruising, pallor, fatigue/weakness). Iron deficiency in an adult should prompt consideraration for testing for Celiac Disease.

- GI symptoms (abdominal pain, bloating, gas, reflux, indigestion, nausea, and diarrhea)

- Lactose intolerance

- Weight loss or falling off normal growth curve in children

- Reproductive conditions: menstrual irregularities, infertility, recurrent miscarriages, delayed puberty

- Oral health conditions: aphthous ulcers, dental enamel abnormalities, geographic tongue (this study showed 15% of patients with geographic tongue have Celiac Disease, 80% of these had no abdominal GI symptoms!)

- Neurologic conditions: peripheral neuropathy, ataxia, epilepsy, concentration and learning difficulties, migraine headaches

- Psychological conditions: depression

- Other: elevated liver enzymes (don’t assume fatty liver!); bone and joint pain

Laboratory Diagnosis:

All tests listed here are covered by Partnership HealthPlan, without any prior authorization requirement.

The first line tests for individuals with symptoms are antibody tests:

- Tissue transglutaminase (TtG) IgA or IgG elevated

- Endomysial (EMA) IgA elevated

- Total IgA

- Deaminated gliadin peptide (DGP) IgA and/or IgG present

These can be ordered in a panel from Quest Diagnositics: the Celiac Disease Diagnositc Panel uses lab code: 15681.

The Celiac Disease Diagnostic Panel has a hyperlink: http://www.questdiagnostics.com/testcenter/TestDetail.action?tabName=OrderingInfo&ntc=15681&searchString=

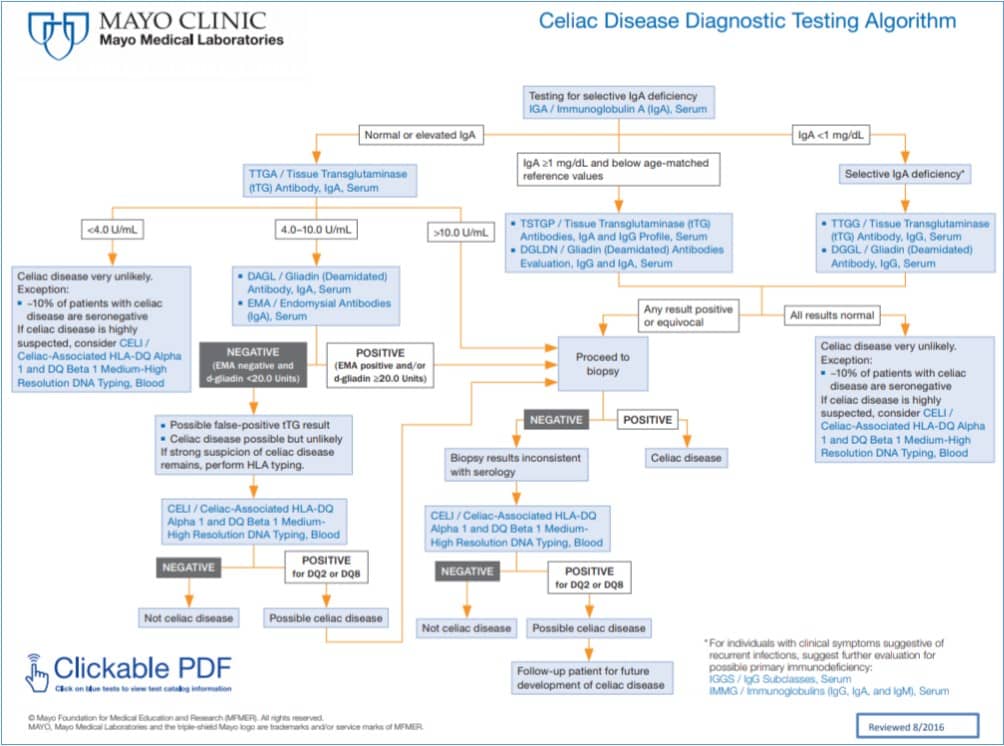

Having noted these potential tests, the algorithm for using these antibody tests with the tests below is complex; the Mayo Clinic algorithm is a good example.

Genetic tests for HLA DQ2 and DQ8 can be ordered through all major laboratories serving PHC patients. As noted above, this is best used to rule out Celiac disease or to test for genetic predisposition in families with Celiac Disease. The Quest lab code is 17135 (HLA typing for Celiac Disease). Like most genetic tests, it is expensive and only covered once in a lifetime for an individual patient; it should only be ordered if the clinician is sure it has not been ordered before.

A definitive diagnosis requires intestinal biopsy, conducted by upper endoscopy after a period of time consuming gluten daily. During the endoscopy, villous atrophy is often noted visually. Re-biopsy several months after being on a traditional gluten-free diet is required, as 20% of individuals with Celiac Disease also have intolerance to the gluten-like proteins in oats, others may react to the gluten-like proteins in corn.

Although not standard in the United States, some European physicians will omit the initial confirmatory biopsy in symptomatic individuals with all 3 of the following:

- Elevated TgG IgA

- Elevated EMA IgA

- HLA-DQ2 or HLA-DQ8 positive.

Note that this is different than the practice in the Unites States, which always a confirmatory biopsy for cases very suspicious of Celiac disease.

Case Follow Up:

As noted above, the diagnosis of geographic tongue alone gives her a 15% risk of having Celiac Disease. Having a second-degree relative with Celiac-like symptoms probably adds some additional risk; if he had a definitive diagnosis of Celiac, it would be about a 5-10% independent risk for this woman. The prior treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection may have increased her risk as well.

She had positive TgG IgA and EMA IgA, followed by a confirmatory small bowel biopsy. After initiating a gluten free diet focused on avoiding wheat, barley and rye, combined with vitamin supplementation, her abdominal symptoms, anemia, geographic tongue, depression, and migraine headaches all resolved.