By Robert L. Moore, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief Medical Officer

“The only true wisdom is to know that you know nothing.”

— Socrates

Wisdom of the Elders

Tribal community members often hold respect for elders as one of their core values. This respect is shown in many ways such as allowing elders to eat first at communal meals, valuing elders’ knowledge of native languages and traditions, and listening to their wisdom expressed through stories passed down for generations.

These demonstrations of respect were evident at a cultural event recently at the Karuk Kahtishraam Wellness Center in Yreka. Teenagers and young adults watched attentively as one elder taught them how to carve traditional wooden cooking paddles. Another elder displayed his tight-weave basket[1]making skills using willow twigs and aged spruce roots. When lunch was served, tasty frybread tacos and fruit, the elders were invited to serve themselves first. During lunch, several elders recounted stories from their lives, gently conveying the life lessons these stories contained.

Many in the United States use a different word to describe older residents: elderly. Although the difference is subtle, elderly is often used in association with a sense of responsibility to provide care, food, shelter, and entertainment. There is less of a sense respect for the wisdom of their life experiences, more of a sense that interacting with the elderly is necessary from time to time. This is a barrier to older adults feeling a sense of purpose as they age. Dr. Victoria Sweet’s excellent book, “God’s Hotel,” about San Francisco’s Laguna Honda Hospital elaborates on the evolution of modern American society’s conceptualization of our older residents.

Of course, there are exceptions to this. In his famous study of communities around the world where substantial populations live to over age 100, author Dan Buettner found that, in addition to a healthy diet, regular exercise, and six other factors, centenarians had an ongoing sense of purpose for their lives, usually including providing advice and support to the younger members of their families. The term “Blue Zones” is used to describe such communities in the Nuoro province of the Mediterranean island of Sardinia, the Nicoya Peninsula of Costa Rica, and Loma Linda, California.

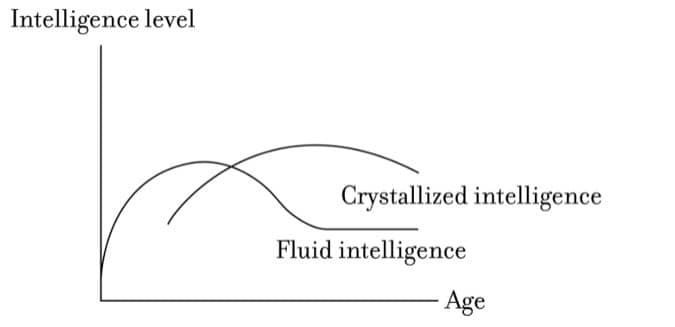

In our early lives, our brains are wired for “fluid intelligence”: the ability to reason and think abstractly and flexibly. This allows us to learn everything from kinesthetic skills like sports or playing a musical instrument to mental reasoning skills involving creative solutions to mathematical or logical problems. As we age, the integration of what we have learned in our lifetimes — from books, other people and from our own experiences — can be manifested in “crystalized intelligence,” sometimes known as accumulated wisdom. Fluid intelligence generally peaks in our 20s and 30s and then declines steadily, whereas crystalized intelligence peaks in our later decades of life. Crystalized intelligence is helpful for teachers, with history professors actually reaching peak intellectual productivity in their 60s and 70s. Interestingly, our ability to learn new words and even new languages can persist well into our older years because the hippocampus, the seat of memory, continues to grow throughout life.

In his book, “From Strength to Strength: Finding Success, Happiness, and Deep Purpose in the Second Half of Life,” economics professor Arthur C. Brooks notes that high-achieving younger professionals who start to decline in their career should intentionally make the jump from the declining fluid intelligence curve to the rising crystalized intelligence curve.

American society celebrates the success of young entrepreneurs, young performing artists, and young scientists who make important breakthrough discoveries that require fluid intelligence. Success in early life, with its attendant public recognition, can make it hard to give it up to make the jump to the second, crystallized intelligence curve. Interestingly, societal belief systems that emphasize the idea that deceased ancestors support those who are living sometimes have more formal ways of recognizing the development of wisdom as a high goal in the second half of life. Confucian stages of life include the ideas of early education, social engagement with accumulation of wisdom in the middle of life, and tapping into the wisdom of elders, sages, and ancestors. As noted earlier, writings summarizing historic and current-day Tribal community values and beliefs include respect for the wisdom of the elders, and the important influence of one’s ancestors on those living today.

A more codified version of these stages is found in the ancient Hindu theory of Ashrama. Ashrama specifies that life should be lived in four stages, each lasting roughly 25 years:

- The first, in childhood and young adulthood, is devoted to learning.

- In the second phase, one focuses on working to build a career and financial stability, as well as to building a family and social connections.

- In the third phase, one retires from personal and professional duties to consolidate their wisdom through teaching and spiritual practices. Moving from the second phase to the third phase is analogous to the shift from the fluid intelligence curve to the crystallized intelligence curve, noted above.

- The fourth phase (if one lives long enough!) is devoted exclusively to spiritual understanding.

Clinician Wisdom

What are the implications of this framework to clinicians?

The scientific framework of evidence-based practice, where activities are tested objectively and rigorously, is at odds with a framework that draws on “ancient wisdom.” In fact, the current standard of care is evolving rapidly. The half-life of medical best practice is roughly five years. Put another way, half of today’s best practices for a given disease condition (e.g., which medication or surgical treatment is the safest and most effective) will no longer be the best practice in five years.

New graduates of physician residency programs, better trained than previous generations in evidence-based practice, will view some of the practices of older physicians as out-of-date. In some ways, though, the skills and experiences of older clinicians integrate knowledge that is not out of date and which younger clinicians would benefit from. Physical exam skills, for example, are becoming a bit of a lost art, resulting in over-use of radiology studies. Surgical skills for non-laparoscopic surgery of older physicians are often impressive, as they had a large volume of such cases before the newer surgical methods became available. Conversely, younger surgeons often have more robust experience with robotic surgery.

Clinicians need to track the evidence base for the conditions they commonly treat. Having a sense of curiosity and skepticism when reviewing the medical literature is key to critically evaluating new knowledge. As clinicians age, the wisdom reflected in their clinical judgement can continue to grow, if they systematically keep up with new knowledge.

Leadership Wisdom

This is also true for clinician leaders, although the nature of new knowledge related to leadership is very different.

Our understanding of the psychological and sociological aspects of human behavior is more scientific than previously, both through more advanced social science research methods, and with greater understanding of how this relates to underlying brain structure and function. The book, “Behave: The Biology of Humans at our Best and Worst,” by Robert Sapolsky is an impressive integration of these fields.

However, clinician leaders generally learn new leadership lessons more slowly, since we are often spending time maintaining our clinical knowledge while concurrently learning business operations and health care policy.

Fortunately, some core leadership wisdom is timeless, and so can be gained through literature, movies, and reading philosophy. An additional vital resource is the crystallized intelligence of our “medical elders,” experienced clinician leaders, such as Dr. Paul Farmer, Dr. Fitzhugh Mullen, and Dr. Anthony Fauci, as well as local clinical leaders in your communities.

To grow and age wisely as clinician leaders, we must embrace the opportunity to absorb the wisdom of elders even while we systematically strive to integrate new evidence-based knowledge!