By Robert L. Moore, MD, MPH, MBA, Chief Medical Officer

“What are the necessary and sufficient conditions for improvement in large systems? Will, ideas and execution!” —Tom Nolan, one of the creators of the Model for Improvement.

In a tribute to Tom Nolan, who died on March 19, 2019, pediatrician and founder of the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Donald Berwick describes what will, ideas, and execution means:

“Providing will refers to the tasks of fostering discomfort with the status quo and attractiveness for the as-yet-unrealized future. Providing ideas means assuring access to alternative designs and ideas worth testing, as opposed to continuing legacy systems. And execution was his term for embedding learning activities and change in the day-to-day work of everyone, beginning with leaders.” —Milbank Quarterly, August, 2019

Nolan’s three conditions, flow roughly in the following order:

- Execution cannot lead to improvement without testing

- Ideas will not be sought out and tested unless organizational leaders make this a personal and organizational priority, an act of will.

It starts with will to improve.

For leaders to decide to make major improvements, fundamentally, we need to challenge the status quo. We must insist on change and provide a vision for a better state that the organization must strive to achieve.

Creating an atmosphere where new ideas can be explored and where strong, independent teams can test these ideas is a central duty of clinical leaders of health care institutions. Yet, it all starts with leadership’s willingness to take risks, communicate a vision of excellence that is achievable, and communicate that the problems of the status quo are unacceptable.

Challenging the status quo is uncomfortable, can be mentally and emotionally draining, and potentially socially isolating.

An alternative leadership style –cherishing tradition and stability– has a certain appeal in the short term. All those staff and stakeholders with an interest in the status quo are happier. There is no need to risk testing new ideas that might fail and make the leader look bad.

When a leader succeeds in upsetting the status quo, particularly in a larger organization, there is significant risk of backlash, which could torpedo the success of the changes. Unless the underlying organizational culture also changes, there is also a probability that improvements will not be sustained and that quality will regress when there is staff turnover.

How do transformational leaders address these challenges? One key tactic is drawing energy from colleagues who are doing the same work in sister organizations. This can help sustain willpower in the face of negative pushback. Another tactic is to develop a group of “true believers” in the quest for quality within different levels of their organization.

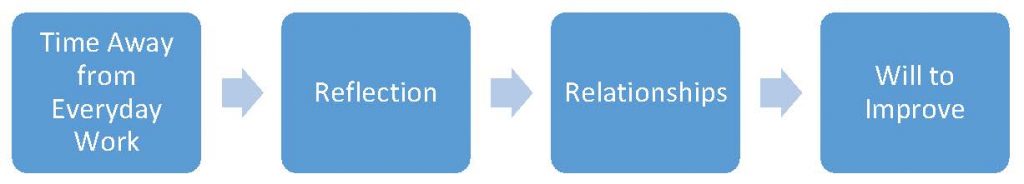

Both of these activities require intentionality. They will not naturally happen in the course of our everyday workweek activities. We need to take some time and mental space to build relationships with colleagues outside our organization and with staff within our organization. These relationships must be based on mutual trust, respect, and a shared dedication to lifetime learning. In short, they require some time for reflection, a critical activity that transformational leaders must ensure they do not neglect.

This suggests a causal chain of activities for transformational leaders to be successful at mobilizing the will to improve:

Clinical leaders overwhelmed with patient care and administrative responsibilities lack the time needed to be transformational leaders. The irony is that an improved/transformed health system can use clinician time more efficiently, ultimately giving more potential time for reflection and cultivating relationships. But how can a clinical leader reach this state of improved efficiency if they don’t have time to reflect on the system they are working in?

If the health care system has capacity to add clinical capacity, this can alleviate time pressures for the clinical leaders. This is certainly ideal, if at all possible. Focus first and foremost on recruiting excellent clinicians with a similar dedication to improving quality.

The other options are to work longer hours (which can lead to family stress), or to disappear from everyday work periodically to attend conferences, read books or listen to podcasts, or even complete formal leadership training. This time away can impact patient care in the short term.

Of course, a combination of these three factors –more staffing, longer hours, and disappearing from everyday work– may also give sufficient time for reflective time and building relationships. Indeed, most transformational leaders have used this combination tactic for their finding time to work on their initial transformational activities.